FFN Video: 7:32-8:45

My paternal grandmother, my maa maa, was my first non-parental caregiver. I, and eventually my sister, stayed at her quiet house six to seven days a week while my parents worked. She would take us on bus rides into DC’s Chinatown where she’d visit friends and play mahjong. She would find greens on our walks and pull them for soups. She would steam whole tilapia and praise my sister for being bold enough to eat the best part, the eyes. Under her watch, I drew monsters, picked fruit from her tree, and scared myself in the dusty basement. I spent many hours there, sometimes bored, sometimes excited, never hungry, always taken care of.

When I was a little older, my maternal grandmother and grandfather, my po po and gung gung, moved to the United States and into our small townhome. They became the primary caregivers for me, my sister, and my cousin. Po Po was the most energetic of my grandparents. She would fold paper into a giant goldfish, one chopstick to hold it up and another to operate the gaping mouth. She would play hand games and leave my too-slow hands stinging. Gung Gung was quiet and would approvingly watch me read out loud or watch animal shows. When my grandparents had the day to themselves, they would pick up Pokémon cards.

Later, my second sister arrived, and we moved away from my grandparents to a bigger house in a much whiter neighborhood and it was clear my experiences under the safe affirming care of my grandparents were vastly different. She went into center-based care, where she would sometimes come back with stories of judgmental, unkind children. As I grew older and had space to reflect, I recognized the racism my sister faced. And later still, I was able to recognize those experiences as “microaggressions” though they did not feel small to my sister. I would be a teen watching my sisters myself before I realized that I knew a lot more Cantonese than them, due to my early years in FFN child care only conversing with my grandparents who spoke little English. Though I lacked the language and context at the time, it was difficult for me to be cognizant of such dynamics, I can now say I am a second-generation immigrant or a third culture kid. As I reflect, my experience with FFN child care helped me stay rooted to my culture, language, and the traditions I still cherish and honor.

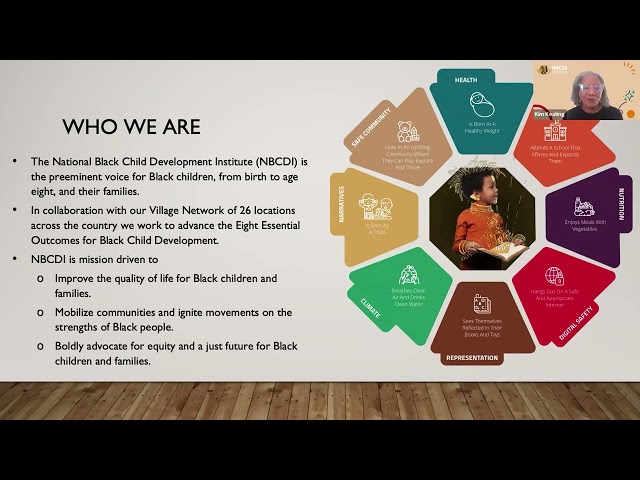

It was not until I came to the National Black Child Development Institute (NBCDI) and became more immersed in conversations about child care policy and FFN care that I fully recognized the boon I received experiencing safe and affirming care through my family. FFN care felt so natural and ingrained in my childhood that I had difficulty grasping those with such strong opposition to it; it was shocking to learn how strong that opposition can be. In the Afrofuturist Explorations led by NBCDI in collaboration with the National Village Network—where we are documenting and elevating the true narratives and desired futures of this form of child care across Black communities—I see reflections of my own story. During our internal conversations with our Village Leaderswe surfaced the existing mental models—assumptions, values, and beliefs—that undervalue FFN care, which helped me understand how dominant narratives diverge from powerful true lived experiences and certainly don’t reflect my own experiences with FFN child care.

My work at NBCDI has also helped me form an understanding of how anti-FFN care narratives are so strongly informed by anti-Blackness. Much of the anti-FFN sentiment is driven by unspoken anti-Blackness and the resistance to trusting Black people—and Black women in particular— to be experts and decisionmakers. When we can begin uprooting the current anti-Black mental models that drive how we develop and implement policy, we can start creating the culture and policies that support every child having the right child care that fully meets their needs.